Antidepressants Can Work, But Only If You Believe They Will

“Sure, I agree that cleaning up your diet and meditating can help with depression, but how can you say that antidepressants don’t work? Prozac saved my sister’s life!”

Do you know someone who suffered from debilitating depression or anxiety, and their life seemingly turned around after they were prescribed antidepressants? I can’t even count the number of times that someone has told me, either in person or as an online comment, a version of this story. But was it the chemical activity of the antidepressant that lifted their mood, or was it their belief that their disorder was being effectively treated? Could the placebo effect – the process whereby your beliefs influence your health outcomes – be at play?

I’ve written extensively about how the placebo effect works and how it even accounts for the ‘benefits’ of antidepressants like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Despite the evidence showing the power of our minds to optimize our health, many dismiss the placebo effect because of the assumption that chemical drugs work through their specific “mechanism of action” – but now, I’m excited to share the provocative results of a new, well-designed study examining the placebo effect.

In this randomized clinical trial

– the gold standard for evaluating medical treatments – people with social anxiety disorder (SAD) were randomly divided into two groups, an ‘overt’ and ‘covert’ group. Everyone was given 20 mg of a commonly-prescribed SSRI, escitalopram (Lexapro), for 9 weeks. In the overt group, people were told that they were being prescribed Lexapro, but in the covert group, people were told that they were given an “active placebo” that had similar side effects as the SSRI but had no clinical effects – even though they were given the same dosage of Lexapro as the overt group.

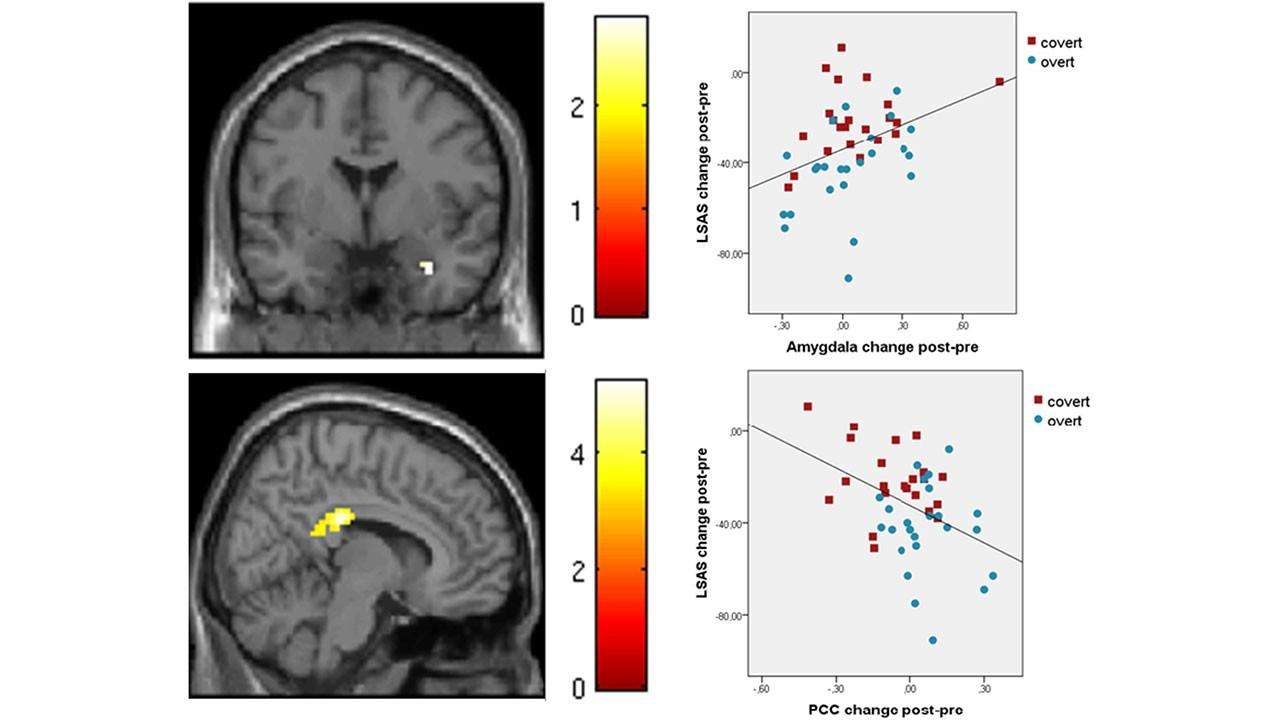

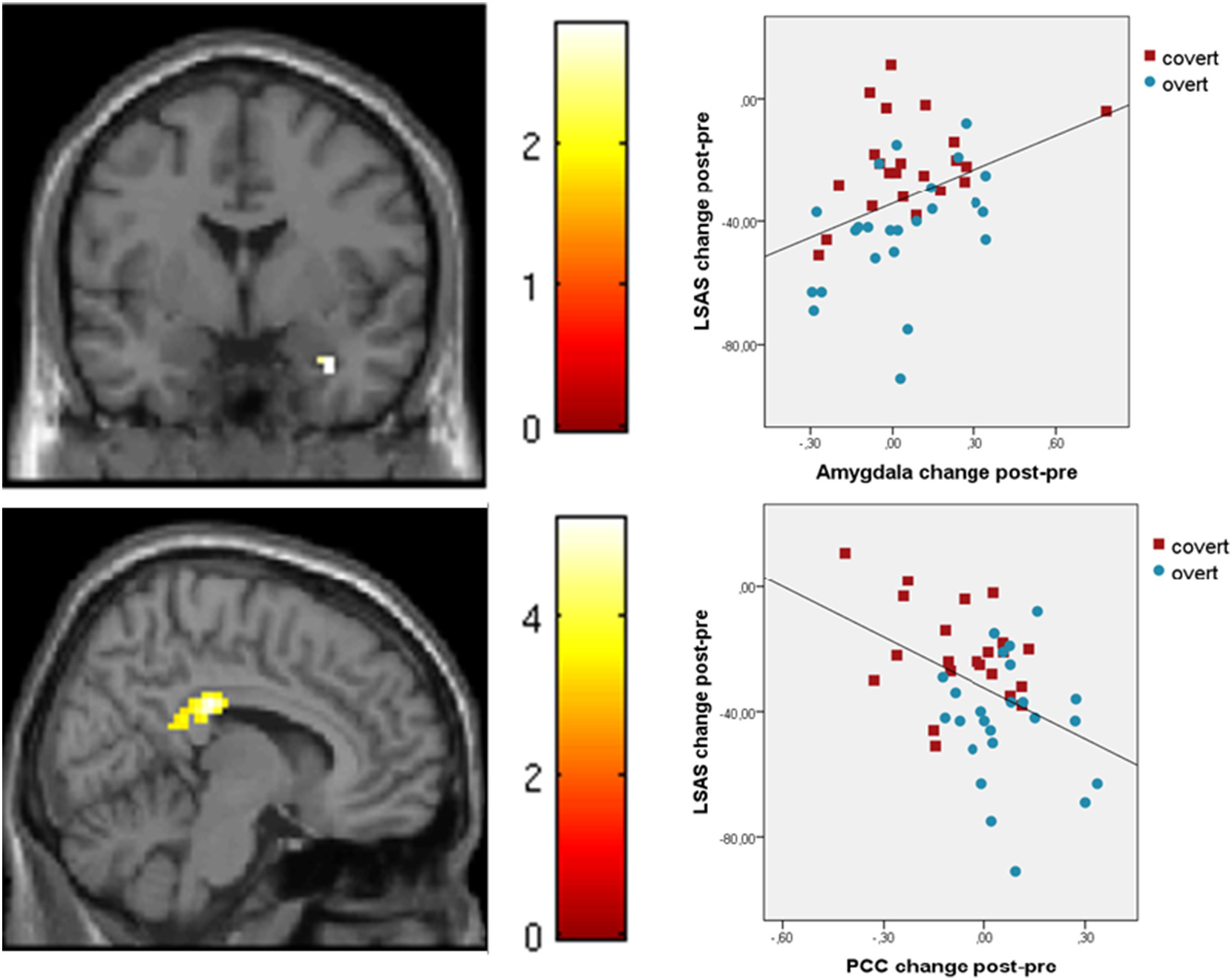

Their progress was monitored by self-rating scales, clinical evaluation criteria, and fMRI scans, a type of brain imaging that measures the activity of brain regions. The results speak for themselves.

Even though both groups received the same SSRI dosages, 50% of people in the overt group responded to treatment, while the response rate in the covert group was a mere 14%. In fact, blood serum analyses confirmed that people in both groups had the same amount of Lexapro and its metabolites in their bodies. The only difference in their treatment was what they were told.

Nearly four times as many people showed clinically significant improvement on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale when they were told that they were receiving an SSRI instead of an active placebo.

This wasn’t the only result that showed that belief about treatment influenced its effectiveness. Quality of life assessments were double in the overt arm compared to the covert arm.

People in the overt group enjoyed reduced anxiety scores over the course of the study compared to people receiving the same SSRI dosage but told they were receiving a placebo.

Brain scans showed a different neurological responses between the overt and covert groups. Generally speaking, people in the the overt group showed increased neuronal reactivity in brain regions that are associated with cognition, attention, and rumination, namely the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC)

and the left mid temporal and inferior frontal gyri.

Perhaps the knowledge that they were receiving an SSRI kicked off a cascade of thoughts about getting better.

Further, the amygdala, the brain region associated with fear-based fight-or-flight responses,

showed different effects in terms of activation and connectivity based on the information given about treatments. For example, people in the covert group exhibited increased activation of the amygdala and connectivity between the amygdala and the PCC, which tracked with higher levels of anxiety.

Brain activity patterns were different in people in the overt group versus the covert group, and these brain activation patterns correlated with changes in anxiety scores.

These researchers performed several other analyses to confirm that the verbal introductions of treatments affected both brain activity and clinical outcomes.

So, do you believe it now?

Do you believe that belief is the most powerful predictor of clinical outcomes in psychiatry? If you are someone who likes a good scientific study to back up your theories, this is one for the record.

Sit with what this study means to you. Because we are wired for belief. In fact, even atheists and skeptics have put their faith and trust somewhere, so perhaps the most empowering thing we can do is to simply examine, expose, and understand what it is that we actually believe. To know this is to lay the tracks that your human experience and potential for healing will naturally follow. Shift your mindset to encompass what’s possible, and the formerly impossible will become real for you.

http://www.ebiomedicine.com/article/S2352-3964(17)30385-7/abstract

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3891440/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2845804/

Want to continue reading?

Enter your details below to read more and receive updates via email.